In our fast-paced corporate world, juggling multiple tasks at once has become a badge of honor. Colleagues often take pride in their ability to multitask, believing it optimizes their productivity. However, the notion of multitasking is a myth. What is often considered multitasking is, in fact, task-switching, and it comes at a cost.

A common example of ‘multitasking’ in a professional setting is attempting to reply to an email while participating in a daily standup call. This often results in a “could you please repeat that?” scenario. Cognitively, our attention rapidly alternates between tasks, a process known as task-switching. Some are better, or rather faster, than others.

Here is a simple and engaging activity to illustrate the cost of task-switching using just a sheet of paper and a pencil. You will be challenged with filling out a three-column chart as quickly and accurately as possible with a specific sequence: Column 1 (Numbers 1–10), Column 2 (Letters A–J), and Column 3 (Roman Numerals I–X). Provided below is a before and after for reference.

| 1-10 | A-J | I-X | |

| Row 1 | |||

| Row 2 | |||

| Row 3 | |||

| Row … | … | … | … |

| Row 10 |

| 1-10 | A-J | I-X | |

| Row 1 | 1 | A | I |

| Row 2 | 2 | B | II |

| Row 3 | 3 | C | III |

| Row … | … | … | … |

| Row 10 | 10 | J | X |

Begin a timer and attempt to fill the squares in column order. Record your time. Then, reset the timer and attempt to fill the boxes in row order. Notice the difference in speed and confusion when switching between numbers, letters, and Roman numerals rather than completing each column in its entirety?

Numerous studies support our simple anecdotal test. Similar research was conducted in Thomas Buser and Noemi Peter’s Multitasking1. Subjects were tasked with solving a Sudoku puzzle and doing wordsearch. It was found that task-switching resulted in decreased productivity. Furthermore, the drop in performance was directly related to the number of switches, indicating that the more a subject switched tasks, the worse their performance was. Lastly, and interestingly, subjects who decided when to switch tasks only did slightly better than those forced to switch. Having shown the detriments of task-switching, it’s important to know why performance deteriorates while switching.

The Flow State

Hungarian-American psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi coined the term “theory of flow” back in 1970. Flow is a state of hyper-focus and mental immersion in an activity. It’s described by heightened concentration, loss of time awareness, and a diminished sense of bodily needs, such as not feeling hungry. Often, athletes will refer to this as ‘being in the zone’, or my new favorite, ‘locked in’.

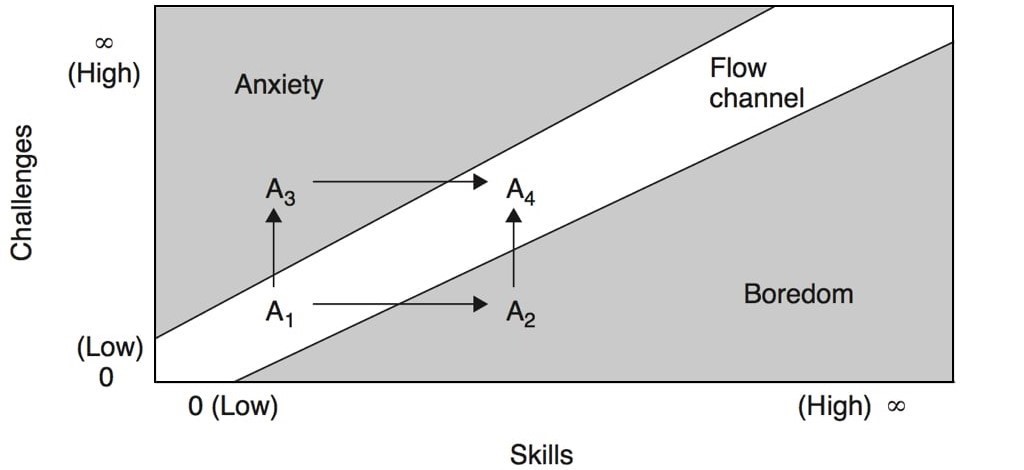

Flow is typically induced by having a clear goal that is challenging and equally meets one’s abilities. Alongside flow are a multitude of other categories used to describe a mental state. For instance, anxiety is a highly challenging situation paired with a low level of capability. Take a moment to review the below diagram and think of a time when you’ve fallen into a specific distinction.

As previously mentioned, to achieve flow, the specific challenge needs to match one’s unique skills. Therefore, flow can be experienced at any level of competition or competency, as it’s subjective to one’s abilities. However, it is often flaunted at higher levels of performance. To enter a flow state, it will require adaptation to the challenge or the individual’s skills.

A learning pianist, A1, playing Hot Crust Buns will move towards Boredom, A2, and will require a more difficult piece to enter back into Flow, A4.

Overall, flow is an interesting concept showing the relation between performance and mental state. It also illustrates the importance of stretching outside of the comfort zone to grow. It boosts intelligence and confidence and leads to a state of happiness.

Downfalls of Disruptions

After combining the knowledge of flow and task switching, it can be deduced that people perform better by completing a task in its entirety without disruption. An interruption could be anything from a simple Microsoft Teams message to a colleague stopping by your desk. In an interview, Gloria Mark of UC Irvine stated, “It takes an average of 23 minutes and 15 seconds to get back to the [original] task.”.4

Continually, she investigated the mental state of those interrupted in the workplace. She found that those who had been interrupted had higher levels of stress, frustration, and slightly higher levels of effort and time pressure. The time pressure enhanced the challenge, leading the subject into a state of anxiety.5

| Mental Workload | Stress | Frustration | Time Pressure | Effort | |

| No Interruption | 10.02 | 6.92 | 4.73 | 11.02 | 9.50 |

| Interruption | 10.83 | 9.46 | 6.63 | 12.69 | 11.04 |

David Frohlich of the University of Surrey conducted an interesting study on the potential benefits gained during human interruptions at the workplace. While conducting the study, he also found that 41% of interruptions in the workplace resulted in discontinuing the interrupted task beyond the duration of the interruption itself.6 The caveat here is that sometimes the interruption was beneficial to the recipient, the person being interrupted.

The Solution: Prioritization

In the busy and disruptive world we live in, effective time management is vital for maintaining productivity without feeling overwhelmed. It allows us to focus on tasks that matter most, ensuring we have ample time to complete our work. Here are three strategies that can help you manage your time more effectively:

Timeboxing: This is the first step where you block off your calendar for deep work and turn off non-urgent notifications. This uninterrupted time allows you to focus intensely and complete tasks efficiently, ideally in a state of flow. It’s important to start with this step, as it’s a proactive step in avoiding interruptions and sets the foundation for focused work.

Ready-to-Resume Plan: After a period of deep work (or during), there might be interruptions or breaks; having a note or plan ready ensures that you can quickly resume work without confusion and continue the momentum.

Evaluating and Adapting: Finally, using tools like the Eisenhower Matrix helps in prioritizing tasks based on their importance and urgency. This step is necessary to ensure that your efforts are directed towards the most salient tasks, thereby preventing any bottlenecks in an ever-changing workplace.

Following these strategies ensures a smooth workflow, minimizes interruptions, and enhances overall productivity. It’s a systematic approach to managing your tasks and time effectively.

- Buser, Thomas, and Noémi Péter. “Multitasking.” Experimental Economics, vol. 641–655, no. 4, 6 Mar. 2012, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-012-9318-8 ↩︎

- Anderson, Henry. “Game Theory – Flow (Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi).” Henry Anderson, 29 Sept. 2016, henryganderson.wordpress.com/2016/09/29/game-theory-flow-mihaly-csikszentmihalyi. ↩︎

- “Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience.” Goodreads, www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/66354. ↩︎

- Pattison, Kermit. “Worker, Interrupted: The Cost of Task Switching.” Fast Company, 28 July 2008, www.fastcompany.com/944128/worker-interrupted-cost-task-switching. ↩︎

- Mark, Gloria, et al. The Cost of Interrupted Work. 6 Apr. 2008, https://doi.org/10.1145/1357054.1357072. ↩︎

- O’Connail, B., and David Mark Frohlich. “Timespace in the Workplace: Dealing With Interruptions.” ResearchGate, Jan. 1995, www.researchgate.net/publication/309903121_Timespace_in_the_workplace_Dealing_with_interruptions. ↩︎