The principal-agent problem is a fundamental issue within organizational leadership that arises when a principal (such as a company’s shareholders) delegates decision-making authority to an agent (like a CEO). The problem lies in aligning the interests of the principal and agent, as both parties may have different objectives. This article explores incentivization strategies to mitigate the principal-agent problem.

The principal-agent problem is rooted in two main issues: information asymmetry and differing goals. Information asymmetry occurs when one party has more information than the other and differing goals are dependent on interests.

Examples in the Real World

The principal-agent problem is all around. Perhaps a doctor is overprescribing tests, a lawyer is trying to bill more hours, mechanics are overcharging helpless individuals, or a homeowners association is not allowing dogs while being months behind on maintenance. Over and over again, the average person is left feeling taken advantage of, simply because others are focused on achieving another objective.

In application, it’s often a sad and mentally irking situation, so please be a decent person.

Examples in the Business World

The most notorious cases are scandals, such as Enron in 2001. The American energy company was caught in an infamous accounting scandal, cooking the books to hide debt from investors. This caused a peak stock price of $90 to plummet into bankruptcy within a year. Afterwards, criminal charges came forth to those accused, and President George W. Bush signed into action the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, protecting investors from similar fraudulent practices.

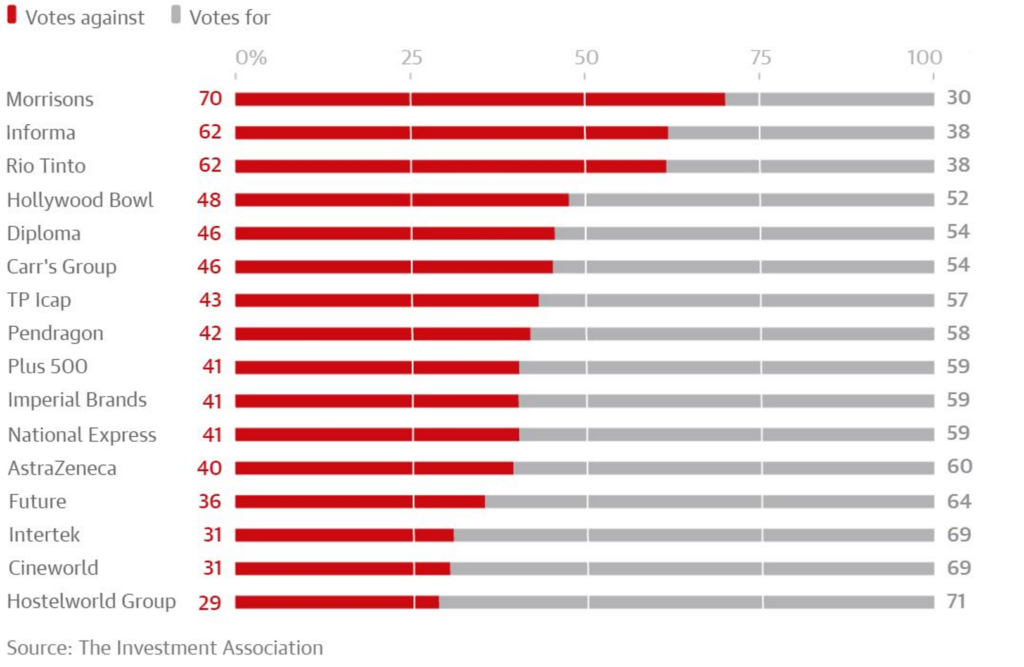

The Invest Association provided statistics on shareholders disapproval of large executive bonuses, especially when having an underperforming stock price. Similar to the NYSE, some of the United Kingdom’s FTSE 100 were ranked.

If a leader’s reward structure is monetarily tied to hitting metrics, deadlines, or objectives, such as a bonus incentive, they are often tuned to make short-term decisions with non-optimal outcomes. Although personally benefited, the leaders fail to adhere to the principal, the shareholders, who desire long-term gains. This extrinsic reward system is not ideal given the use case. These may be large capital examples, but as mentioned before, the principal-agent problem occurs at all levels of work.

The Principal-Agent Issue

Most businesses operate on an extrinsic motivation system for validating employees. Seen simply as ‘work hard and receive more money’. However, there’s slightly more detail on the extrinsic side of motivation. An extrinsic motivation can come from positive reinforcement, a reward, or negative reinforcement, such as avoiding punishments.

Here are common extrinsic examples you may see today:

- Positive Reinforcement: financial gain, promotions, recognition, or bonuses.

- Negative Reinforcement: performance improvement plans, repeating tasks, receiving a talking-to, or working overtime due to missed deadlines.

The issue here is that extrinsic motivation is only half the formula.

Due to a multitude of reasons, Americans are valuing quality of life more now than ever. In a recent study, people were asked if they would take a 20% pay cut for a better quality of life. Remarkably, the majority of younger generations would prefer work-life balance.

In the United States Sixty percent of millennials, people aged 27 to 42, would accept less money for a better work-life balance. Fifty-six percent of Generation Z adults, people aged 18 up to 26, said the same thing. Compared to the thirty-three percent of Baby Boomers aged 59 to 77.

Further with Ford2

This leads to the other, and growing, side of the motivation spectrum.

Intrinsic Motivation

People prefer living a happy life. They want to spend time with their pets, loved ones, pursuing hobbies, or endlessly scrolling social media. A farmer may be fulfilled by a ‘hard day’s work’, an artist by pursing mastery of their craft, or a philanthropist building their charity. To each their own.

Quite paradoxically, most businesses have a principal-agent problem in providing their employees with the correct type of motivation. They focus strongly on pay, which is a growing misalignment amongst those entering the workforce.

Instead, corporations should pursue the interests of the individual employee. Conduct behavioral assessments, receive feedback on different reward structures, or allow for job rotations. All of these strategies allow the company to become enlightened on the individual’s own desires, and then, and only then, can they be properly motivated.

Here is a short list of innovative companies chasing intrinsic motivation.

- Google: During Google’s IPO, Founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin mentioned what came to be known as the 20% policy. “We encourage our employees, in addition to their regular projects, to spend 20% of their time working on what they think will most benefit Google. This empowers them to be more creative and innovative. Many of our significant advances have happened in this manner. For example, AdSense for content and Google News were both prototyped in “20% time.”3

- Southwest Airlines: Their purpose statement reads, “Connect People to what’s important in their lives through friendly, reliable, and low-cost air travel.”4

- Zappos: “The Offer”. Zappos offers $2,000, on-top of training pay, for employees who believe they are not a good fit for the company culture. Allowing both parties to be happy if the employee chooses to leave.5

Motivational Caveats

Firstly, expectations need to be set early, ideally not change, and reinforced often. Once the line in the sand is erased, it’s impossible to find and significantly harder to reestablish given the loss of credibility. The typical idiom is “give an inch and they’ll take a mile.”

Secondly, when giving positive or negative reinforcement, whether it be intrinsic or extrinsic, it needs to be done appropriately, both justly and promptly. It’s obvious to not give a raise to someone underperforming. However, it’s much harder, given human nature and empathy, to not subtlety validate someone who’s underperforming. This is shown by not providing a negative reinforcement equal to the issue, at or near after, the time of the incident.

Conclusion

More now than ever, companies need to adapt their strategies to maintain and motivate employees. Zappos has a unique tactic for hiring talent, while traditionally companies highlight their benefit packages to entice candidates. This too is an issue, like the principal-agent problem, that can be fixed by putting a focus on learning more about the individual. As Ted Lasso or Walt Whitman said, “Be curious, not judgmental.”. For an enjoyable read on an eccentric hiring process, please read the Golden Mean of Higher.

- Jolly, Jasper. “Executive Pay: Big Names That Fell Foul of Shareholders.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 26 June 2021, www.theguardian.com/business/2021/jun/26/executive-pay-big-names-that-fell-foul-of-shareholders. ↩︎

- “Working for Balance – Further with Ford 2024: Ford Motor Company.” Working for Balance – Further with Ford 2024 | Ford Motor Company, 2024, corporate.ford.com/microsites/ford-trends-2024/working-for-balance.html. ↩︎

- Page, Larry, and Sergey Brin. “Founders’ IPO Letter.” Alphabet Investor Relations, 18 Aug. 2004, abc.xyz/investor/founders-letters/ipo-letter/. ↩︎

- Gallo, Carmine. “Southwest Airlines Motivates Its Employees with a Purpose Bigger than a Paycheck.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 10 July 2020, www.forbes.com/sites/carminegallo/2014/01/21/southwest-airlines-motivates-its-employees-with-a-purpose-bigger-than-a-paycheck/. ↩︎

- Taylor, Bill. “Why Zappos Pays New Employees to Quit–and You Should Too.” Harvard Business Review, 19 May 2008, hbr.org/2008/05/why-zappos-pays-new-employees. ↩︎